Queen B—Alfa Garrison, B-1

People

Sunday, October 6, 2024

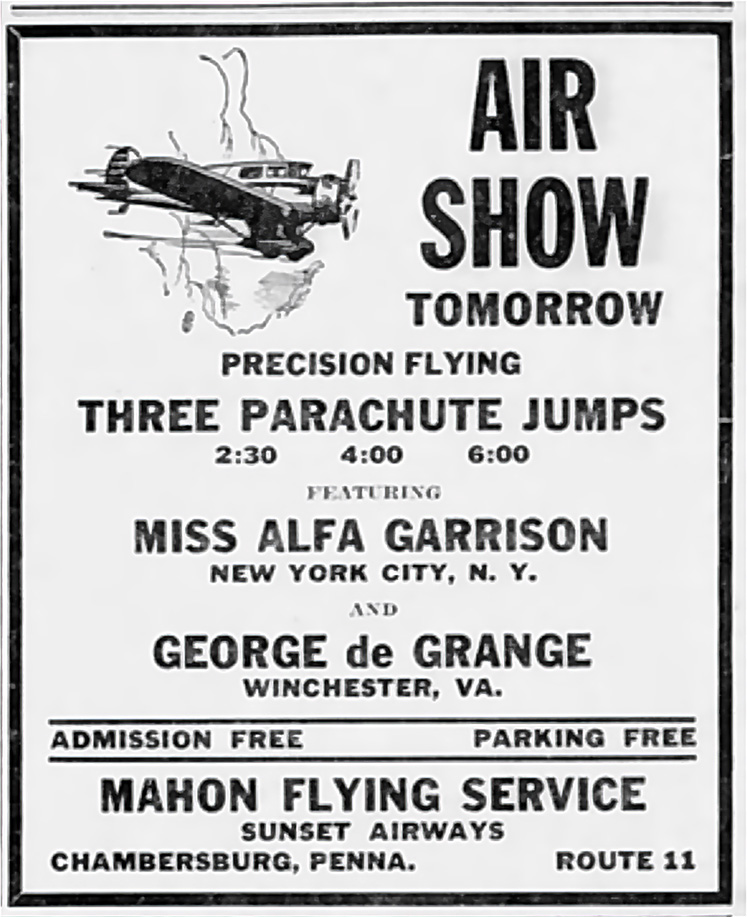

Above: Joe Crane, C-1, and Alfa Garrison, B-1.

Many skydivers know that Lew Sanborn received the first D license. Others may know that Jacques-André Istel received the first instuctor rating. Fewer know that they decided this by a coin toss, with Istel winning and choosing I-1 (a numbering system that USPA eventually discontinued).

But what about the first recipients of the lower-level license categories? Who, for instance, received license number B-1?

The answer to that question has been clouded by time, but information has recently emerged, brought to the light of day by one important phone call. And thanks to a phone call, another fascinating chapter of our sport’s history has been made accessible. We can now add another name to the list of women pioneers of parachuting, alongside Jeanne Garnerin, Käthe Paulus, Tiny Broadwick and Adeline Gray (to name a few).

But First, A Little History

Joe “Jumping Jack” Crane, C-1, is generally accepted as the father of sport parachuting in the United States. Crane was born in 1902, before Orville and Wilbur Wright were household names, and was in elementary school in Springfield, Illinois, when Albert Berry made the first parachute drop from an airplane in flight at nearby Lambert Field. Crane would soon be billed as “The World’s Marvel Parachute Jumper,” joining the Army Air Service in 1920 and making the first of his 15 military jumps in 1923.

After his 1924 discharge, Crane spent time as a steeplejack before pursuing parachuting as a full-time career, signing on with the Burns Flying Circus in 1925, when he made a then-record 2,250-foot freefall, disproving common misconceptions that a person would lose consciousness, spin wildly or even explode in those circumstances.

After his 1924 discharge, Crane spent time as a steeplejack before pursuing parachuting as a full-time career, signing on with the Burns Flying Circus in 1925, when he made a then-record 2,250-foot freefall, disproving common misconceptions that a person would lose consciousness, spin wildly or even explode in those circumstances.

Stunt jumping at carnivals and fairs was completely unregulated, and “spot jumping” (or accuracy) contests seem to have fit right into this new “Golden Age of Aviation” during the 1920s. Crane, jumping an unsteerable 24-foot round parachute, won many of those competitions and by 1929 was the national spot-jumping champion, a distinction that he would earn again 1931 and 1932.

When the 1933 National Balloon Races were held in Chicago, Crane offered his services in organizing a spot-jumping contest. Not only was his request denied, but the National Aeronautic Association told him that he was not allowed to participate himself. Undaunted, Crane wrote a letter of protest, claiming that the NAA had no jurisdiction over parachutists because they did not issue licenses. The NAA accepted a second application from Crane and as a result began issuing licenses to sport parachutists in 1933. Crane was on the board of experts that established guidelines for those licenses, and when the National Parachute Jumpers Association (NPJA) formed, it was with him as its head.

The World War II Years

While Joe Crane was making a name for himself with his intrepidity, others were dreaming of plummeting through the clouds just like Jumping Jack. Two of those dreamers, both ladies, would credit Crane as their inspiration to become parachute jumpers and riggers. One of those ladies was Adeline Gray, an employee of Pioneer Parachute Company of Manchester, Connecticut (and subject of “Adeline Gray—Daredevil in Nylon,” August 2021 Parachutist). The other woman, who would become the first B-licensed skydiver, is the subject of this article.

Alfa Roberta “A.R.” Garrison was born October 21, 1916. By the late 1930s she had established herself as a stunt jumper, and went to work as a rigger for Crane’s Mineola parachute rigging loft on Long Island, New York, at Roosevelt Field—a hub of aviation activity. Garrison was an expert parachute rigger and serious businesswoman; the July 18, 1944 Newsday magazine featured her for her superb rigging and repair skills.

Crane trusted Garrison’s rigging ability and business acumen so much that when he volunteered to return to active duty, aiding the allied cause with his own rigging talents, he promoted her and announced in the April 1942 NPJA newsletter that he was temporarily turning over management of both his parachuting business and the sport’s association to Miss A.R. Garrison, noting “… and there’s no danger she’ll be called in the draft.”

Garrison composed the association’s newsletters from mid-1942 onward, and was officially elected to the top position by NPJA members later that year. In turn, Garrison saw Crane as a father figure and mentor—she gave Crane sole authority to handle her affairs “in the event of an accident,” and continued her professional relationship with him for the rest of her life.

After World War II ended, many returning paratroopers and pilots wanted to continue the camaraderie and excitement of flying and parachuting, and massive numbers of surplus parachutes, containers and rigging gear were being decommissioned and sold for pennies (or just discarded). As the gear entered the civilian world, so did many riggers finishing their military service. They needed organization.

That’s why Crane and Garrison decided to change the NPJA (which was basically a union advocating for fair standards in pay and safety for exhibition jumpers) into the new National Parachute Jumpers and Riggers Inc (NPJR) in 1946. Who better to lead this new organization than Joe Crane … and A.R. Garrison?

The First FAI Licenses

On May 16, 1946, Garrison was the signatory of record for the Articles of Incorporation when Joe Crane’s NPJA became NPJR, the official beginning of the organization that eventually became the Parachute Club of America, then the United States Parachute Association. Crane was president, while Garrison served as both secretary and treasurer, as well as editor of the new NPJR newsletter (the predecessor of today’s Parachutist).

The association oversaw the introduction of regulations for certifying riggers, the types of parachutes they could pack and currency requirements for both gear and riggers themselves. NPJR became fully recognized by the NAA, which in turn represented the sport as a representative to the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI)—the worldwide governing body for air sports competitions. In 1947, the FAI began issuing licenses to U.S. jumpers through the NAA and NPJR.

In those days, an A license required 10 jumps, a B license required 20 and a C license required 100. There was no D license yet. Joe Crane took C-1, and for B-1, the choice was A.R. Garrison.

In the following years, the formidable pair at the helm of NPJR turned their attention to making sport parachuting safer, including creating legislation for the mandatory use of reserve parachutes, limits on wind speed and rules concerning the training of new parachute jumpers. In the early 1950s, they worked diligently to establish competition rules, with plans of putting together an American parachuting team to compete internationally. Garrison was in the first class of parachuting “stewards” (what we would now call “judges”), experts appointed to officiate at parachuting meets and certify records. France, the U.S.S.R. and a few other nations had already begun organizing sport jumping clubs. Sgt. Fred Mason would be the first of many Americans to compete in the FAI World Parachuting Championships in 1954, the event’s fourth year.

A Sad Ending to a Magnificent Beginning

Alfa Roberta Garrison was considered fun-loving, independent, incredibly intelligent, physically attractive, brave and sensitive. To quote her niece, Deborah Eck, “It comes with pure intrigue that this young woman had an inner stirring that had to be explored and satiated … leaving behind her comfortable midwestern roots, where dad was a farmer and a teacher, her mother a homemaker, with her one sister a nurse and the other a teacher, to pursue the thrill which this adrenaline-releasing sport provided for her … a wild pony of sorts.” Garrison reached epic status in her family’s folklore, like so many high-achieving members of our small community.

She was not immune to the pressures of the ground, as Joe Crane had mentioned publicly in a 1939 NJPA newsletter his best wishes to Garrison for her fast recovery from a “nervous breakdown.” He was also quoted as saying “This was not due to her jumping, but from overworking herself,” finishing with “Be careful Alfa; parachute jumpers are not supposed to work hard.”

On the evening of Saturday, March 22, 1952, Garrison dined with both Crane and her brother-in-law. There is no record of her final words. Her body was found the next afternoon by her building’s superintendent, after a concerned call from, of course, Joe Crane. “Police listed the death as natural,” reported a local newspaper, “and theorized that the woman dozed while taking a bath.” She was laid to rest next to her mother in a family plot in Hopewell Cemetery near Cincinnati. She was 36.

Memories of A.R. Garrison were nearly lost to history, despite her significance to growing our sport during its infancy—until a young relative of hers decided to do a little research into her legendary great-aunt. Garrison’s great-niece Jenna asked her relatives enough questions to lead them to a line in the July 2021 Parachutist, at the beginning of “The First 75,” an article about the first USPA D-license holders: “... a jumper by the name of A.R. Garrison, about whom little is now known, received B-1.”

They also found her Bible, which contained preserved documents such as Garrison’s airman’s card, letters, will (written to Joe Crane), newspaper articles and more. With a little bit of help from the internet, those tucked-away family memories found their way to the International Skydiving Museum and then to USPA.

Garrison was a woman in a man’s world, using only her initials in official written correspondence (which was a common practice for women in business at the time). She was vital to Crane’s business and dedicated to the safety of her parachutists and their gear. Her legacy is one of contributing, with long-lasting effort, to advancing parachuting safety and laying the groundwork for an eventual U.S. Parachute Team. She was not only knowledgeable about parachute rigging and administration, but also an expert jumper. Over 70 years later, more than 40,000 USPA members have Garrison to thank for the sport they love today.

Garrison received some of the recognition she richly deserves, albeit posthumously. Nearly a dozen of Alfa’s family were present during the annual International Skydiving Museum & Hall of Fame Celebration Weekend at Skydive Chicago on September 27. Her family was presented with honors from the museum and USPA to “commemorate the discovery and many achievements of Alfa Garrison, B-1, as a true pioneer of our sport.”

About the Author

Bob Lewis, C-29597, has spent decades contributing to skydiving through his photography, research and writings. In 2020, the International Skydiving Museum & Hall of Fame presented Lewis with its Trustees’ Award.