Tales from the Bonfire | The Tomato Patch Landing

It was the early 1960s, and we were at Naval Air Station Grosse Ile in Michigan (now a municipal airport), the last stop on a string of air shows that had taken us from coast to coast. As Chuting Stars, the U.S. Navy Parachute Exhibition Team, we were in high demand, and we often appeared at air shows alongside the Navy’s Flight Demonstration Team, the Blue Angels. We were recruiters for the U.S. Navy, and we brought messages of opportunities in the Navy to high school students by arriving at their football field in an exciting manner.

Normally, our six-week winter training session was held at the Naval Air Facility at El Centro, California, where weather conditions allowed us to jump every day. We developed four “high show” routines with two to four men making 60-second delayed-opening jumps from 12,500 feet. If weather conditions were poor at an air show, it was instead a hop-and-pop from no less than 2,000 feet. Each member of the team was assigned to a certain spot in the full-altitude routine, and that never changed. There was never a doubt (to the others in a routine) as to where he was or what he was doing during the freefall. Our equipment was state of the art at that time. The back chute was a 28-foot round canopy constructed of low-porosity 1.6 ounce-per-square-yard nylon. It had an 11-panel T-U modification that was several generations advanced from the Derry Slot. (A little side note: Frank Derry invented and patented the “Derry Slot” in 1945. Simply speaking, it was a series of open slits in the seams of the canopy that joined two of the back gores, and was first used by smoke jumpers to provide them the ability to rotate their canopy during descent and, to a small degree, control their landing location.)

The reserve chute was a 26-foot conical, onto which we mounted an altimeter and stopwatch. The altimeter simply confirmed what you already knew in your head after so many jumps, and that was when it was time to dump. The stopwatch ensured precision in each freefall. On a high-altitude routine, each member would punch their stopwatch at the same moment as they were about to exit the aircraft, and they then could make the maneuvers the routine called for at a precise time.

For example: Two jumpers would exit, with the first one turning 180 degrees to track away from the aircraft heading. The other would track on the heading of the aircraft. At exactly 25 seconds, both would fire their flare guns, make a 180-degree turn to track back past each other, then again fire their flare guns just before pulling their ripcords at 2,500 feet. With smoke trailing from cans attached to their boots and flares bursting in the sky, this routine was quite spectacular. When asked how I could pull the ripcord with a flare gun in each hand, I’d say “With my teeth!” On hazy days, when it would be difficult to see an aircraft flying at 12,500 feet, we would fire a flare out the aircraft door just before jumpers would exit for each routine, in order to help the audience focus on the right spot in the sky.

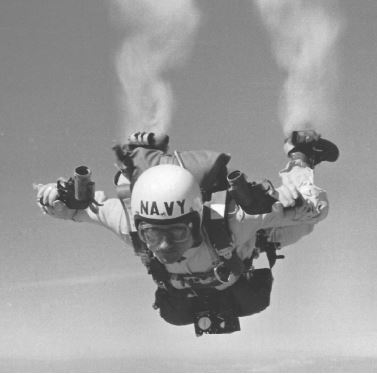

Ed Kruse experiements with a wrist-mounted camera.

Kruse makes a skydive with two flare guns.

The day of the Grosse Ile Air Show was clear, but we were pushing the wind limit. We were the main event, however, and we didn’t want to disappoint the large audience in attendance. Also, our public information officer wanted a few photos, some with a water background, for the packets he sent to air show sponsors. Fellow “Star” Tony Riek and I were given the task. Tony—a young guy from Wisconsin, was the best relative work jumper I’ve ever known. I was jumping with a wrist-mounted 35mm manual-advance camera. Tony would maneuver in close to me, but with the tiny camera viewfinder I could usually sight in for four or five pictures.

We opened close to each other over the waterway that separates the U.S. and Canada, and in harmony we said, “Oh darn,” (or words to that effect). We were close to the Canada side, but if we landed there we might be arrested for illegal entry. We turned to the west, hoping we’d run out of water before we ran out of air. Houses packed the shoreline, and the street behind them had the highest electric lines man ever put up. Houses also lined the other side of the street, but we were lucky there was one with a large garden. We went “splat,” right into their tomato patch.

The homeowner just happened to be working in his yard and asked where our plane went down. After we explained what had happened, he asked, “I’ve got to have a drink; how about you guys?” We told him we were on duty, and couldn’t have a drink. But he broke out a couple bottles of something, and I think we must’ve had root beer.

Soon there was a helicopter hovering over the garden looking for us. Tony went out, gave them a thumbs-up, and held his drink high as he waved them away. We could now relax and have a couple more root beers, waiting for a vehicle to pick us up.

Ed Kruse | D-121 and I-18

Burnsville, Minnesota