Tales from the Bonfire | What I Wish I Knew About Concussions Sooner

Above: Photo by Mike McGowan.

Originally published on May 23, 2023, on neuronsloading.wordpress.com.

Whether you’ve thought of it this way before or not, skydiving is a contact sport. And as the scuff marks on our helmets show, we get hit in the head—a lot. From striking the door to freefall collisions to hard openings, there are countless ways to end up with a head injury in the air.

And yet, unlike more traditional contact sports (football, soccer, hockey, etc.), the skydiving industry today lacks formal protocols and procedures for dealing with head injuries. It’s really up to us to be informed and make smart decisions on our own for our bodies. Prior to my concussions, I knew very little about brain injuries. I am still not a doctor, but I do want to share what I have learned through my own experience and education from my care teams to hopefully help others.

I don’t think I would have done anything differently to prevent my first concussion, but I could have prevented the second (and all of the complicated, lingering symptoms) by simply not blindly returning so soon. If I could go back in time knowing what I know now, I can confidently say I would stay home from that camp.

Competitive skydivers are often high achievers who don’t like to miss out or let others down. And canceling plans or halting a training day can be expensive, inconvenient for your teammates and organizers and gut-wrenching for your soul. But you shouldn’t be thinking about how expensive your canopy is when you cut away, so similarly try to keep that one camp in perspective when you’re talking about the health of your brain and your mind. There will always be more camps and events, but there is only one you. You only get one brain.

Numbers Game

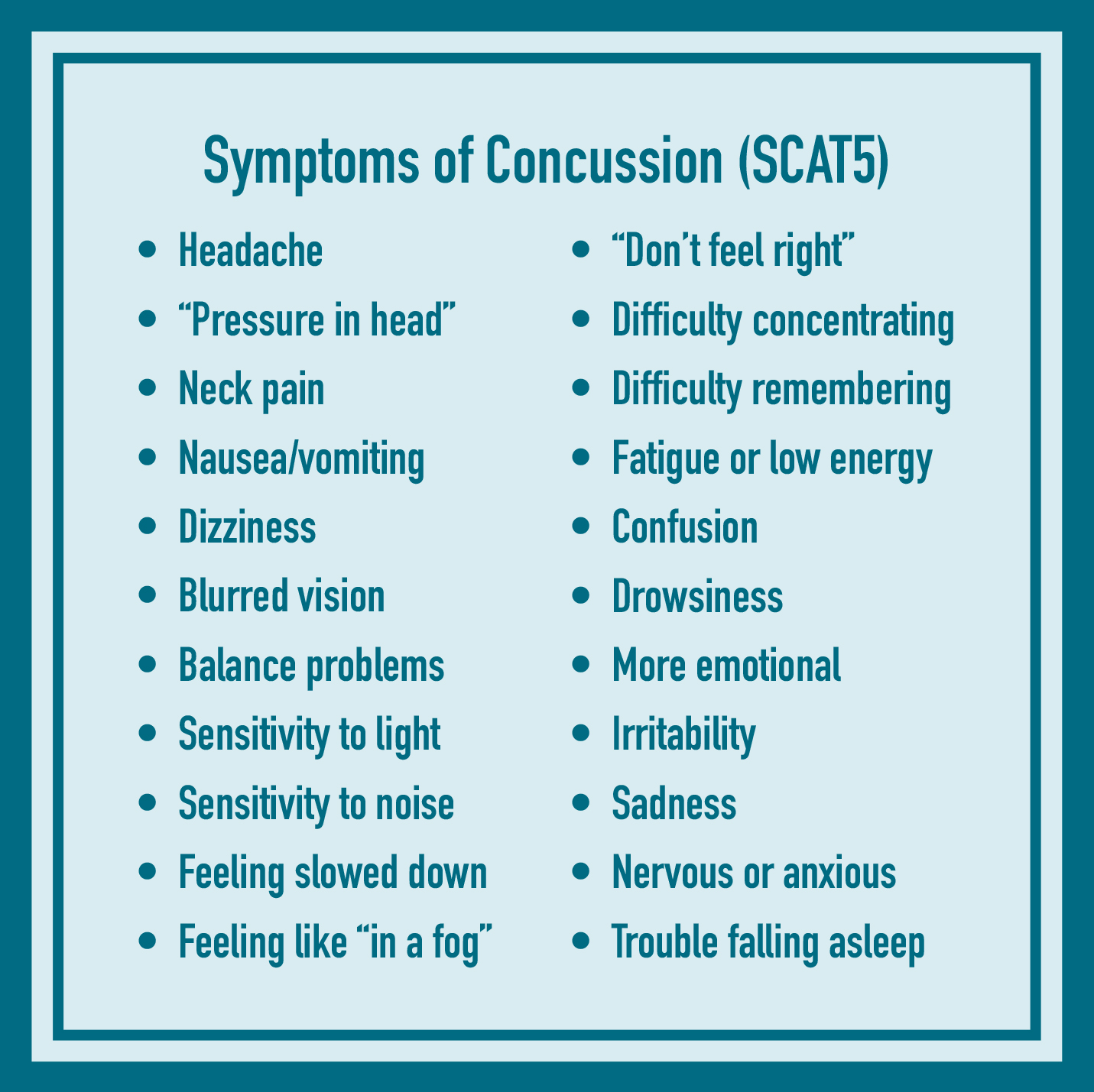

There is no single test for a concussion, and most concussions are (inconveniently) not visible on CT scans or MRIs. However, there are a number of clinically validated assessments and questionnaires that help evaluate suspected concussions. Some common tools are ImPACT, SCAT5 and King-Devick, which you can read more about online. These tools cover a variety of symptoms and functions, from a simple headache to working memory to eyes scanning across a page.

Many professional athletes will conduct a baseline test using one or more of these tools—that is, they’ll take the test or answer the questions when they’re feeling normal, before an incident occurs. Then, if an athlete has a suspected concussion during play, they can retake the test (in some cases, on the sidelines) to help identify the presence and severity of concussion symptoms. Through recovery, the athlete can retake the tests regularly to assess progress, determine when they have returned to their personal baseline, and identify a safer window to return to play.

Many professional athletes will conduct a baseline test using one or more of these tools—that is, they’ll take the test or answer the questions when they’re feeling normal, before an incident occurs. Then, if an athlete has a suspected concussion during play, they can retake the test (in some cases, on the sidelines) to help identify the presence and severity of concussion symptoms. Through recovery, the athlete can retake the tests regularly to assess progress, determine when they have returned to their personal baseline, and identify a safer window to return to play.

I would love to see more competitive skydiving athletes seek out baseline testing via a neurology or sports medicine clinic. An obvious challenge here is the limited access that many professional skydiving athletes have to high-quality health insurance and healthcare. More discussion and creativity will be needed to figure out how to increase athletes’ access to neurological evaluation (and if you’re reading this, I’d love your thoughts). But if you do have good healthcare, I’d encourage you to look into this testing for yourself.

Healthcare

After my first concussion, I did not seek medical care, in part because I did not know where to go. My concussion did not seem serious enough for the emergency room, but I didn’t see how a family doctor could help me, either. However, time is critical. The sooner you get started with the right type of care, the better your outcomes will likely be.

Your first stop as a concussed athlete is often times the emergency room or urgent care. Your doctor will evaluate your initial symptoms, get you started on home care, and rule out more severe injuries, such as skull fractures or brain hemorrhages.

After that, I would suggest seeking out either a neurologist (ideally, a neuropsychologist) or a sports medicine physician for follow-up as a concussed athlete. Within these fields, you may also be able to find a specialist who has a special interest in concussions, works in a concussion clinic or “return to play” clinic or treats a local professional or collegiate sports team. These types of doctors are well-positioned to properly guide you on safely returning to your sport.

You might be wondering if you can work with your normal family doctor for concussion follow-up. This could be appropriate for concussions from car accidents or falls, but in my opinion is not typically sufficient for athletes. Unlike concussions from freak accidents, athletes are returning to an arena in which they are very likely to encounter more trauma to the head. The vast majority of physicians have specialization in other areas and are not experts in tracking concussion symptoms over time and guiding decisions about readiness to endure more head trauma. A physician with experience working with injured athletes will be better equipped to track your progress and make a plan based on your personal risk profile.

Return to Play

Returning to competition after a concussion is a step-by-step process. It’s not as simple as, “My symptoms are gone, so I’m going to the meet this weekend.” After an initial period of 24-48 hours of rest, there is a gradual increase in physical activity that takes 1-2 weeks at a minimum.

The purpose of a phased approach is to reduce the risk of sustaining a second concussion while the brain is still vulnerable to injury from the first. During this window, it is easier to get a second concussion, and there is an increased risk of more severe, longer lasting symptoms. Additionally, physical and mental activity often makes concussion symptoms worse, so this “ramp up” model of returning to play can uncover symptoms that are hiding under the surface during rest. Take the time to listen to your body and ramp up patiently.

Here is an example of what a Return-to-Play model could look like for skydivers, based on an adaptation that my physical therapist and I worked on together:

1| Symptom-Limited Activity: Daily activities that do not provoke symptoms (e.g. work, school)

2| Light Aerobic Exercise: Walking or stationary biking at a low to medium pace. No resistance training.

3| Sport-Specific Exercise: Tunnel flying one-on-one. Move on all planes (up/down, side-to-side, slow rotation) and watch for reintroduction or worsening symptoms.

4| Non-Contact Training Drills: More challenging tunnel drills — introduce faster rotation and more head movement. Potentially hop-and-pops (to reduce the risk of concussion from a hard opening). Resistance training.

5| Full-Contact Practice: After medical clearance, participate in normal training activities.

6| Return to Play: Normal competition.

Take It Seriously

Although neither of my concussions were overly traumatic on their own (I know people that have come back from far worse trauma), my doctors and I believe my prolonged symptoms are due to incurring two concussions close together in time. I cannot emphasize enough that your brain influences everything about you and your body. When your brain signals go rogue, the effects range from inconvenient to debilitating. There have even been some cases when getting two concussions very close together in time has been fatal. So the moral is: Take the first one seriously, follow the protocols, and treat your brain with the respect and care it deserves.

Kelsey Strock | D-40422

Casa Grande, Arizona