The 2023 Non-Fatal Incident Summary—Part One: Landing Incidents

Over the decades, the skydiving community has played a pivotal role in the trend of decreasing skydiving fatalities. Actively participating in non-fatal incident reporting helps USPA identify areas where our sport’s safety and training standards can be enhanced. While our goal is a year with zero fatalities, it’s crucial to understand that zero fatalities wouldn’t imply skydiving is a safe sport. Skydiving is inherently risky, but it can be done sustainably with the right measures. Ensuring sustainability in skydiving requires us to be constantly vigilant, and continuing to report non-fatal incidents presents an opportunity for us to learn, adapt and improve our safety measures.

In 2023, the skydiving community in the United States made approximately 3.65 million jumps, marking a 6% decrease from the previous year—though that still ranks as the second-highest recorded annual jump volume. The rise in reported incidents, however, is significant, with USPA receiving 328 reports, a 10% increase from 2022.

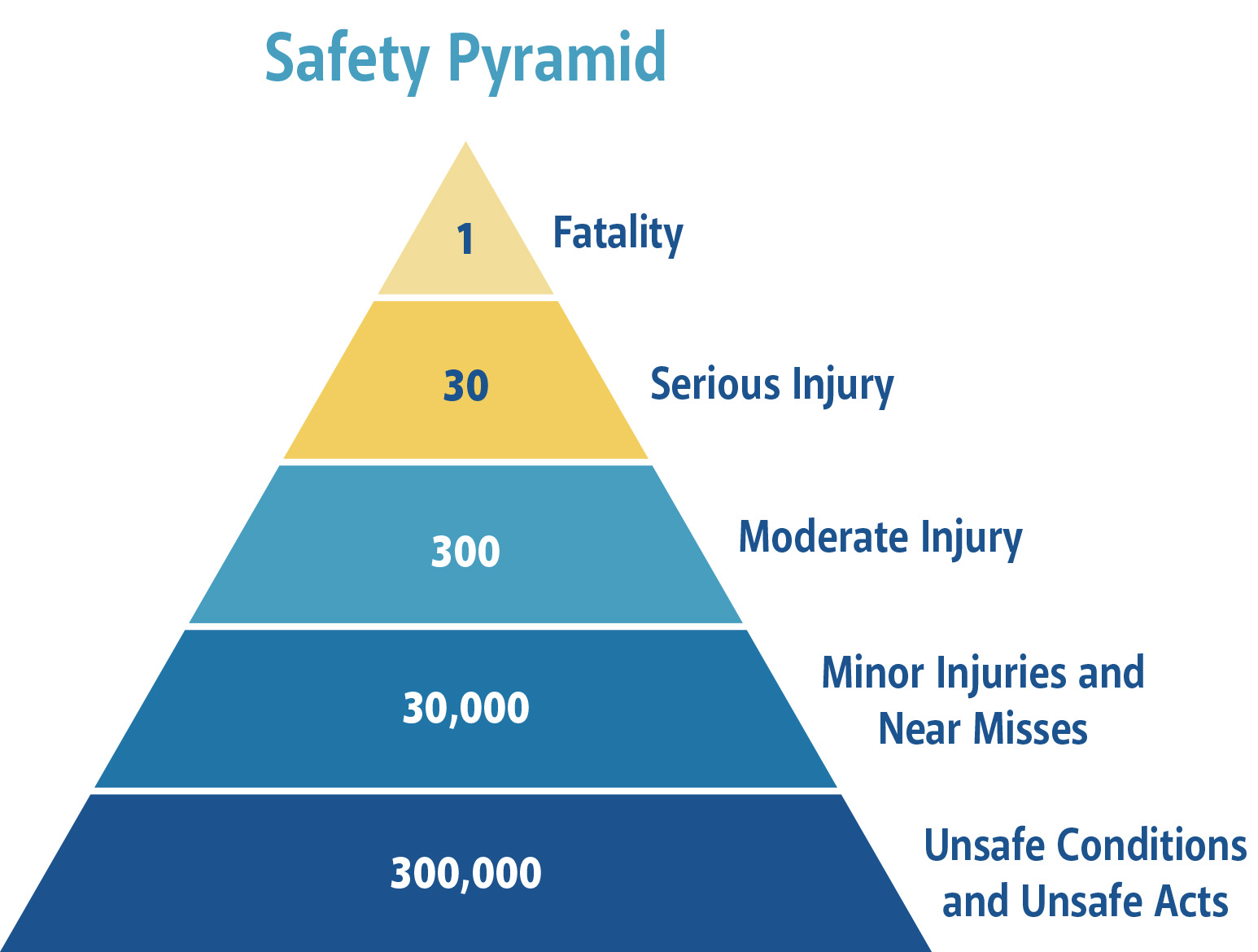

That being said, much of the data is influenced by underreporting by most of the skydiving community. The Safety Pyramid, which Herbert Heinrich introduced in 1931 after examining 70,000 industrial accidents and which Frank Bird expanded in 1966 through his study of more than 1.5 million accident reports, illustrates a connection between different degrees of injuries and fatalities.

Applying their theories to the four intentional-low-turn fatalities in 2023 suggests we should have seen around 1,200 reports in this category alone. When considering the broader picture and comparing it with data from other skydiving associations, USPA estimates that, based on the number of jumps in the United States, we should receive about 6,000 reports annually. This significant discrepancy points to a potential gap in our incident reporting, underscoring the need for a higher level of compliance from our membership to capture all incidents, major and minor.

The Injury Severity Index (ISI)

The Injury Severity Index (ISI)

In this report, we utilize an Injury Severity Index (ISI) that categorizes on a scale of 0 to 5 the severity of injuries sustained during incidents.

0 No Injury

1 Soft-tissue injury typically requiring only local first aid

2 One broken bone or multiple breaks of a single bone or joint and dislocations

3 Multiple broken bones

4 Traumatic brain or spinal cord injury

5 Fatal (not included in this report)

In the following sections, we categorize non-fatal landing incidents by their primary causes and display the percentage each category represents. Lacking extensive historical data, we compare 2022’s figures with the 2019-2022 average to identify trends and target safety improvements.

Landing Issues: 114, 48.1% (2019–2022: 57.2%)

Three subcategories of landing problems—each requiring different areas of training to prevent—compromise the overarching category. These subcategories of landing problems are:

- Intentional low turns: purposeful high-performance maneuvers for landing. These usually involve a jumper initiating a high-performance turn at an altitude too low for the parachute to return to straight and level flight before reaching the ground.

- Unintentional low turns: unplanned low turns, usually to avoid other parachutes in the air or obstacles on the ground.

- Non-turn-related: includes improper landing techniques, landing on obstacles or encountering other hazards (such as deep water) while under a properly functioning parachute.

Landing issues decreased 9% in 2023 from the prior year. In 2019 and 2020, landing issues accounted for 60% of incident reports; in 2021 and 2022, they slightly declined to 57%. However, without complete reporting compliance, it is hard to tell if landing issues have dropped or if members are just not reporting their landing issues as much as in prior years.

Intentional Low Turns: 21, 8.9% (2019–2022: 9.1%)

The data collected in 2023 accentuates the risks of executing high-performance canopy maneuvers during landings. The higher the degree of the turn and the higher the wing loading, the more severe the injuries tend to be. Less-experienced jumpers usually use larger canopies and make turns of less than 180 degrees, so they mostly incurred minor injuries, often due to misjudged flares or ineffective parachute landing falls (PLFs). Conversely, USPA’s data indicates the tendency for more-seasoned jumpers to engage in larger turns at higher wing loadings, which leads them to sustain more-severe injuries.

Two incidents in particular highlight the need for jumpers to refine their flare techniques and practice PLFs. In these cases, one jumper broke a wrist and the other an ankle after gaining speed from a turn but attempting to flare as they would have for a straight-in approach, which propelled them upward at the end of the flare. Neither jumper performed a correct PLF. Adding speed to landings alters the timing of the flare and the precision required for a safe touchdown, so jumpers should learn these techniques at a safe altitude in a stuctured environment before using them near the ground and always be prepared to PLF if something goes wrong.

One intentional-low-turn incident had many lessons to teach regarding currency, experience and downsizing. A B-licensed jumper with 350 total jumps, all in the past 12 months, was flying a 150-square-foot canopy at a wing loading of 1.33:1 and attempted a 180-degree front-riser turn too close to the ground. The jumper broke his tibia, fibia, knee, ankle, hip and three vertebrae and had a spinal hemorrhage. Fortunately, medical professionals are optimistic that he will regain the ability to walk.

This near-fatal incident highlights that while frequent jumping (currency) is beneficial, it doesn’t replace the comprehensive skill set and nuanced understanding developed through extended, varied experience. Despite accumulating 350 jumps within a year, this jumper was flying a smaller canopy than the Skydiver’s Information Manual advises for someone with his experience and exit weight. Being current helps with familiarity, but true expertise is honed slowly over time and through diverse landing challenges.

Given his experience and time in the sport, it’s also likely that this jumper recently transitioned to a smaller canopy. A common assumption among skydivers is that their skills and familiarity with one canopy will seamlessly transfer to a new, often smaller one. However, each canopy has unique flight characteristics, and jumpers must dedicate time to understanding and adapting to these nuances before executing maneuvers they were comfortable with on their previous canopy.

The 2024 Safety Day campaign “Stay Alive—Practice Five” introduced a downsizing checklist to address many of the issues associated with low turns. This resource guides jumpers through the essential steps before and after downsizing their canopies. USPA strongly recommends that any jumper contemplating a switch to a smaller canopy or changing planforms download and thoroughly review this checklist from uspa.org/safetyday.

Unintentional Low Turns: 2, 0.84% (2019-2022–5.82%)

In 2023, no fatalities were associated with unintentional low turns, a notable improvement from previous years. All skydivers involved in such incidents reported only minor injuries, with an average ISI of 1. This figure is significantly lower than the averages in prior years, with 2022 having an average ISI of 2.85 and 2021 at 2.45.

Data compiled since 2021 indicates that students and A- and B-licensed jumpers are most likely to make unintentional low turns. Oftentimes, this follows a recent transition to a smaller canopy. This change sometimes introduces unfamiliar flight characteristics, leading to misjudgments, especially when the new canopy reacts differently than expected, potentially placing the jumper in unexpected, risky situations like a head-on approach toward an obstacle.

There were two reported incidents in this category in 2023: a B-licensed jumper who turned low during an off-field landing to avoid trees and a D-licensed jumper who performed an aggressive turn to avoid colliding with another jumper in the landing pattern after conducting a slow, 360-degree turn to final approach. Spatial awareness and the ability to adapt to dynamic conditions rapidly are both critical when flying a canopy, and these situations reinforce the necessity for continuous training and vigilance, particularly in complex landing scenarios.

Some jumpers stop rehearsing their canopy emergency procedures after becoming licensed. Instructors can help mitigate these problems by emphasizing canopy emergency procedures during student training and reminding their graduates to continue rehearsing them throughout their skydiving careers.

“Stay Alive—Practice Five” emphasizes this by highlighting five fundamental canopy skills essential for every jumper’s proficiency. The campaign offers video recordings of the seminar to reinforce these skills, available in the downloads section of the Safety Day page on the USPA website. All skydivers, regardless of experience level, would benefit from viewing these videos.

Non-Turn-Related: 91, 38.4% (2019-2022–43.9%)

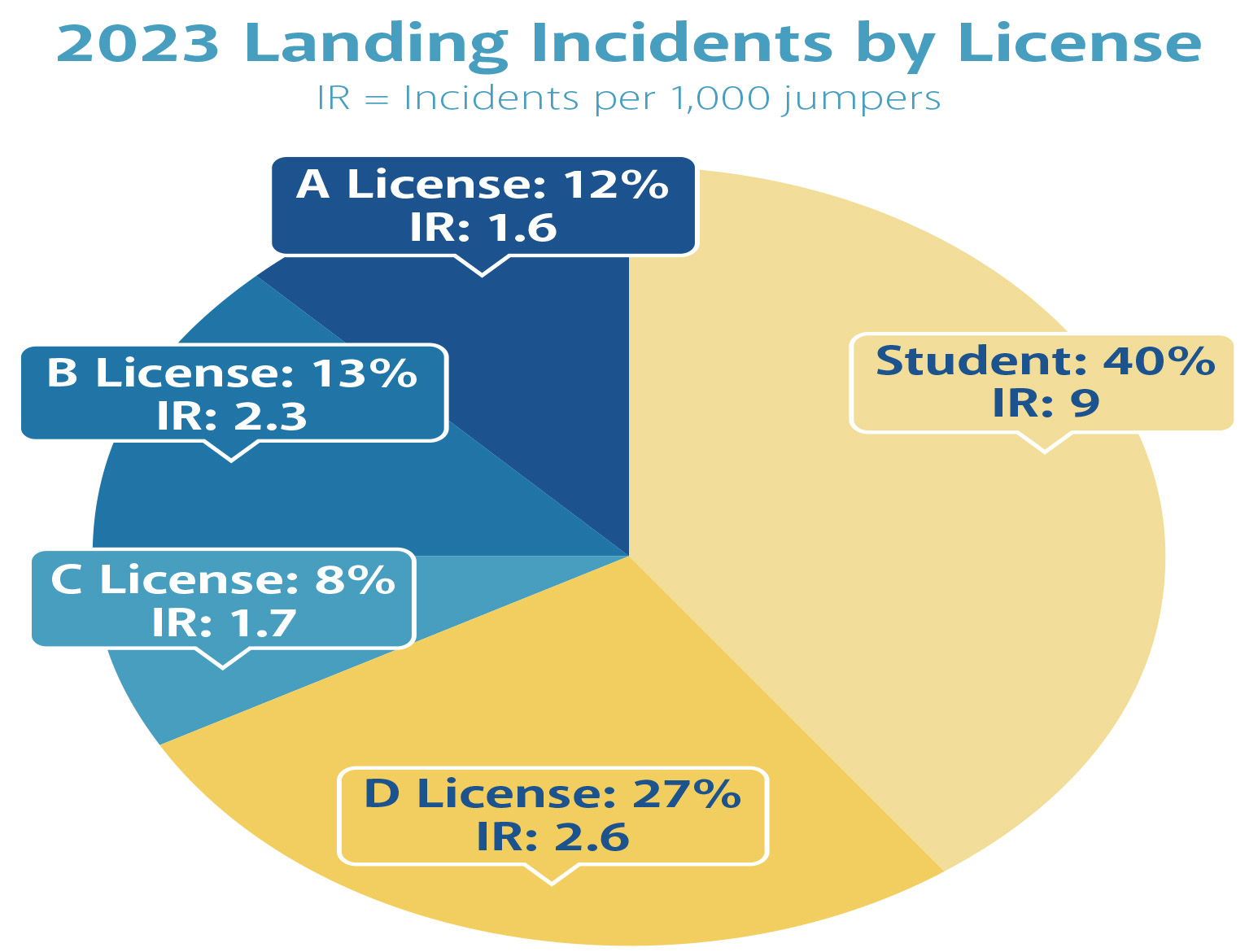

In 2023, there were 91 reports of landing incidents not related to turns, with only two resulting in fatalities. This demonstrates that most issues encountered during straight-in approaches can be managed effectively. Traditionally, less-experienced jumpers have been most associated with this category, but in 2023 D-licensed skydivers made up 27% of these reports—a significant rise from previous years.

In 2023, there were 91 reports of landing incidents not related to turns, with only two resulting in fatalities. This demonstrates that most issues encountered during straight-in approaches can be managed effectively. Traditionally, less-experienced jumpers have been most associated with this category, but in 2023 D-licensed skydivers made up 27% of these reports—a significant rise from previous years.

While a simple tally might suggest that jumpers who hold a certain license are more prone to incidents than others, this approach doesn’t account for the varying numbers of jumpers in each category. To refine our analysis, we developed the incident rate, which calculates incidents per 1,000 jumpers within each category, providing a more equitable comparison. This adjusted view shows that although D-license holders have a higher number of incidents in absolute terms, their incident rate is comparable to those of other licenses when adjusted for population size. The data reveals that students are almost four times more likely to experience non-turn-related incidents than those in any other license category.

To further explore common causes of landing injuries to jumpers, non-turn-related incidents are broken into these subcategories:

- Obstacle: Hit an obstacle

- Distraction: These reports indicated that the jumper was distracted on landing

- Pattern: Performed a poor landing pattern

- Turbulence: Encountered turbulence, and it was the primary cause of the injury

- Flare/PLF: Flared and/or performed a parachute landing fall poorly or not at all

- Tandem: These reports specifically stated that the student or instructor had a poor body position for landing

- Uneven Ground: These jumpers slid in their landings in an inappropriate area

For the fifth consecutive year, the Flare/PLF category has emerged as the predominant cause of non-turn-related incidents in skydiving. 35% of 2023’s incidents in this category were preceded by a poor landing pattern, suggesting that the heightened stress levels experienced during the final approach could impair a jumper’s ability to execute these crucial maneuvers effectively.

A successful landing depends on actions taken before reaching the ground. A well-planned and stress-free pattern, starting at 1,000 feet, provides a solid foundation for the final stages of the descent. This allows jumpers to maintain composure and focus, significantly enhancing their ability to execute a proper flare or PLF.

Flaring problems can be separated into five subcategories. Flaring too early tops the list at 30% of these incidents. In several incidents, jumpers let up on their toggles after realizing they had flared too early. This can have dire consequences as the canopy begins a new flight cycle. Jumpers should stop flaring when they realize they have started their flare too high, holding their brakes and then finishing the remainder at an appropriate altitude.

Flaring too late is the second-most common flare issue, with an ISI of 1.9, slightly higher than the 1.6 ISI for early flares, suggesting late flares are riskier. Not flaring at all has an even higher ISI of 2.4. The most dangerous, however, is the uneven flare, with an ISI of 2.8, often leading to unintentional turns during landing. This typically happens when jumpers reach toward the ground, exacerbating the turn and then forgetting to execute a PLF.

Jumpers should maintain their hands close to their torso during the flare, ensuring even input, which adds more strength to the flare. Concluding the flare, hands should rotate inward toward the bottom and center of the torso, positioning the jumper correctly for a PLF if needed.

The Skydiver’s Information Manual Section 4-A offers crucial guidance: “Be ready to perform a parachute landing fall (PLF) with every landing.” It elaborates, suggesting a stand-up landing if the touchdown is gentle and the skydiver feels stable on their feet. Additionally, the manual advises that a PLF should be executed whenever landing outside the designated airport area. Regular practice of the PLF is essential, ensuring skydivers maintain their skill and readiness to use this technique whenever necessary for a safer landing.

This sport requires a balance of skill, preparation and vigilance. Each incident report is a vital learning opportunity and a stepping stone toward refining our approach to safer landings. However, that sentiment extends to the entire skydive—not just the landing—which we will explore in next month’s Parachutist.

Next Month: The 2023 Non-Fatal Incident Summary—Part Two: Non-Landing Incidents