You People Did What?! | The Long and Sometimes Crazy History of Skydiving Instructional Methods

Part One: Static -Line Through AFF

For everything, there is a first. After all, somebody must come up with an idea and then figure out a way to make it happen. Skydiving student training programs are no different, and the four different first-jump methods available today all began as an idea in someone’s head.

The sport of skydiving has seen significant advances in training over the years. Through it all, no matter which decade or which discipline was under development, there was one common denominator: The individuals involved wanted to improve student safety and also ensure that rating holders received the highest level of training and evaluation possible. It’s been a long, slow process with monumental efforts by hundreds of people along the way.

Today’s skydiving students benefit from all those advances and changes in training, supervision and equipment. In 1976, there were 23 student fatalities and static-line was the only method available for making a first jump or learning to skydive. In 2021, for the first time ever, there were no student fatalities and the number of student jumps completed was probably 10 times the number completed in 1976. There were a lot of painful lessons throughout the years that led to achieving this level of safety. Constant improvements in training and equipment have combined to eliminate as much of the risk as possible, and each rating has a colorful past and interesting development.

Static-Line

In 1906, Charles Broadwick—who traveled the country entertaining crowds with jumps from a hot-air balloon—invented the static-line method of deploying a parachute packed into a backpack-style harness and container. In 1908, Georgia Thompson joined his travelling troupe and took the name Tiny Broadwick. She also made jumps from hot-air balloons and airplanes. In 1914, she demonstrated a parachute jump to the U.S. Army and became entangled in the static line. She cut the static line, deployed the parachute manually and became the first person to make a freefall parachute jump.

Although the military did not utilize static-line deployments during World War I because of unreliable results while exiting from the airplanes of the time, Broadwick and others (including the U.S. military) continued to develop it. By World War II, it had become a reliable method to deliver large numbers of soldiers into battle out of airplanes.

After World War II came to a close, some of those paratroopers wanted to continue jumping for recreation. During those early years of civilian sport parachuting, static-line was the only method of student training available, and the United States Parachute Association (and its two predecessors, National Parachute Jumper and Riggers Association and the Parachute Club of America) had very basic guidelines for training students, all heavily influenced by current or former military jumpers.

Beginning around 1959, PCA began requiring static-line instructors (those who could teach the first-jump course) to simply hold a D License; pass oral, written and practical parachute rigging examinations; and demonstrate the ability to vary horizontal displacement and rate of descent in freefall. However, anyone who made it to 75 jumps and obtained a C License was automatically allowed to jumpmaster (supervise and dispatch from aircraft) static-line students with no additional training required.

As skydiving began to grow in popularity during the early 1960s, concerns over the quality of instruction and the increasing number of student fatalities emerged. The automatic jumpmaster authority for anyone receiving a C License was proving to be problematic. The Federal Aviation Administration was also starting to take notice of the increase in skydiving activity, and the threat of heavy government oversight was lurking in the background.

In 1968, USPA began working toward separating licenses from ratings and developing a new training program for jumpmasters and instructors. USPA adopted the new rating program in 1969 and placed it into service on January 1, 1970. The new Jumpmaster Certification Course (JCC) and Instructor Certification Course (ICC) were both largely modeled after military training courses and helped to improve the quality of instruction and student supervision. Anyone who wanted to act as a jumpmaster for static-line students would now need to attend and pass a JCC. The JCC and ICC continued largely unchanged for the next 30 years, with any updates mainly having to do with improvements in equipment. In 2000, USPA implemented the Integrated Student Program, and the static-line instructor rating program received a much-needed facelift soon after. Since then, the static-line instructor course has remained largely the same.

Instructor-Assisted Deployment

In the 1970s, most licensed jumpers moved away from belly-mounted reserves to dual-parachute backpack containers and ditched spring-loaded main pilot chutes and ripcords in favor of hand-deploy main pilot chutes. This opened the door for a new method of dispatching students out of the airplane using the hand-deploy pilot chute instead of a static line. In Canada in 1979, Tom McCarthy at the Gananoque Sport Parachute Center developed the instructor-assisted-deployment method. Initially, the method involved the instructor holding onto the student’s main pilot chute and extracting the main parachute as the student let go of the airplane. Soon after, Rob Laidlaw modified this by having the instructor throw the main pilot chute. This provided a cleaner main deployment and reduced the chance of the student’s arm entangling with the main bridle. Reminiscing about the development of IAD, Laidlaw remarked that, “Tom was always a forward-thinker.”

IAD worked very well, but for reasons unknown, USPA was somewhat slow to adopt it as a sanctioned first-jump method. In 1981, two drop zones—Alabama Aero Sports and High Adventure Sports in Tennessee—received waivers to use the “jumpmaster-controlled system,” which was simply IAD with a different name. Ten years later, in 1991, USPA issued High Adventure Sports another waiver to continue with what was back to being called “IAD,” along with the Spokane Parachute Club in Washington and NE Pennsylvania Ripcords. USPA expanded the waivers in 1992 to include Oklahoma Skydiving Center, Seven Hills Skydivers in Wisconsin and Connecticut Parachutists Inc., and it renewed the waivers for several earlier-approved drop zones.

USPA Headquarters completed the IAD course syllabus in 1993 and officially approved it for inclusion as a USPA instructional rating in July 1995. The IAD student training program, as well as the instructor certification program, received an update in the early 2000s with the introduction of the Integrated Student Program. Many drop zones continue to offer IAD as a training program for their students today.

Accelerated Freefall

The 1970s saw a large increase in skydiving activity, with many changes in equipment and skydiving techniques. Relative work (now called formation skydiving) was booming, and the sport was seeing a huge influx of young and hip civilian skydivers. New and exciting competitions were taking place, and skydiving boogies were born. By the end of the decade, the wheels were in motion for two new first-jump methods: accelerated freefall and tandem.

Bob Sinclair instructs “The Tonight Show” host Johnny Carson prior to his freefall first jump in 1968.

The Air Force had developed the “buddy jump” freefall training program in the 1960s and 1970s, but civilian freefall training jumps were still in violation of USPA’s Basic Safety Requirements. Nonetheless, they were happening around the country. If a static-line student were having trouble with freefall control, it was not that unusual for a static-line jumpmaster to make a full-altitude harness-hold jump to help the student work out the control issues.

These one-off freefall jumps were different than those that operated under waivers. Paul Poppenhager received a waiver to the BSRs in 1970 to freefall train first-jump students at his DZ in Indiantown, Florida. His program eliminated the static line, with the students exiting and immediately pulling a ripcord for their first five jumps and then moving to longer delays. His waiver remained in place for many years, but the method of training never expanded to other drop zones.

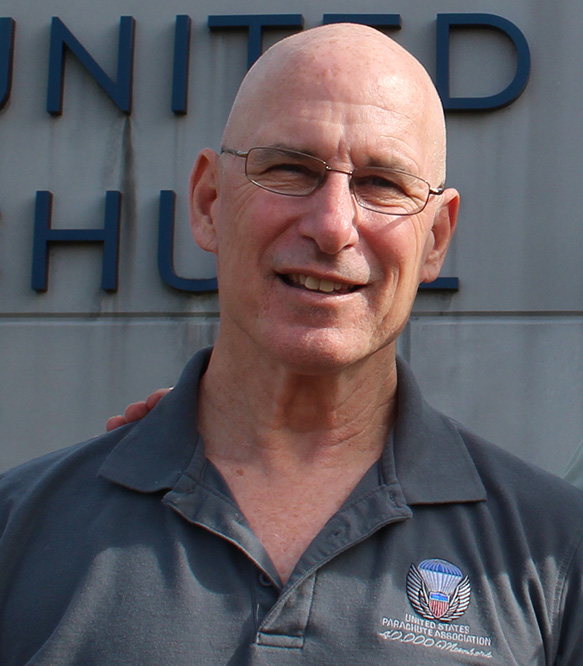

Ken Coleman, a main developer and proponent of AFF student training, passed away in a balloon accident just prior to USPA Board approval of the program.

Ken Coleman, a main developer and proponent of AFF student training, passed away in a balloon accident just prior to USPA Board approval of the program.Perhaps the most famous unsanctioned freefall student jump took place in July 1968 when Bob Sinclair—who worked in Hollywood with Jim Hall of Parachuting Associates Inc. providing aerial stunt work—trained “The Tonight Show” host Johnny Carson for his first jump in Elsinore, California. Carson exited at 12,500 feet with Sinclair holding his harness until Carson pulled his ripcord at 2,500 feet. The footage aired on “The Tonight Show,” and Carson remarked to his audience that it was the most fascinating thing he had ever done. As an editor’s note to the article published in the October 1968 Parachutist about the Carson jump, USPA warned readers that the Basic Safety Requirements allow only for static-line student training and that the freefall buddy system was “not the new way.”

As it turns out, the buddy system, was the new way … it just took another 10 years for it to begin to gain acceptance. In 1978, Ken Coleman hatched a plan for what began to be called the accelerated freefall program. He obtained a waiver from the USPA Board and approached Skydive DeLand owner Gary Dupuis about developing the new student training program there. Dupuis was happy to have Coleman’s experimental program at his Florida drop zone, as he had taken students on harness-hold freefall jumps in the 1960s.

Coleman’s approach towards student freefall training was different from what others had been doing. It included a comprehensive program of seven levels of training that incorporated two jumpmasters for the first three levels, before moving the student to single-jumpmaster jumps. It also incorporated a plan for a certification program to evaluate and rate new AFF jumpmasters and instructors. Based in DeLand, Coleman, T.K. Donle, Dupuis, Rocky Evans, Hoot Gibson, Mike Johnston, Charles Kinlin and John Robbins worked on developing the new program.

The USPA Board approved the AFF program at its September 1981 meeting, but sadly, Coleman died in a balloon accident just before it. Johnston, Al King and Jim Mowery successfully presented the final proposal for the AFF program to the board, and it went into effect in 1982.

Following the board’s approval, the challenge then became initiating a brand-new program and meeting the demands of those who wanted to attend certification courses and earn the new rating. USPA held tight control over the program, with the board approving a very limited number of course directors (now called “examiners”). Courses required a minimum of 10 AFF instructor candidates to schedule, and USPA would not allow another course to be held during the same time within 200 miles of that drop zone. The Safety and Training Department scheduled courses, managed the finances and handled all the other logistics of the program.

Johnston, King, Gregory and Paul Sitter were some of the early course directors, but the job required being on the road almost every week of the year and most got off the treadmill after a year or two (although Sitter stuck it out for four and a half years). In the late 1980s, USPA handed the reins over to Don Yahrling, who was the only course director for the program for the next five years.

As demand for courses continued to increase as the popularity of the AFF program grew, USPA added two more course directors—Billy Rhodes and Rick Horn—in 1994. Both Rhodes and Horn had assisted with many courses, and each had extensive experience evaluating candidates. But demand for AFF instructors (and therefore, course directors) was getting even stronger, and centrally managing the finances, course rosters and schedule also became a logistical nightmare. So, in 2001, USPA eliminated direct financial control of the program and opened the door for adding new AFF course directors, eventually even removing the need for board approval. Now, more than 20 years later, the AFF course is well-established—although standardization between courses is still a challenge—and the number of AFF examiners running courses has exploded to nearly 70.

During the development of the AFF program, Al King (left) and Mike Johnston (right) demonstrate how AFF instructors would grip a student in the air.

Since 1982, the AFF rating course itself has undergone multiple changes. A consistent problem throughout the first two decades of the course was a lack of candidate preparation. The pass rate hovered around the 50% mark, but most of the candidates passed their second course once they knew what was expected of them. Even after USPA created a proficiency card of prerequisites for attending the course, course directors still found that candidates were not prepared when they arrived. In 2001, Glenn Bangs proposed including more training and practice jumps in the rating course before candidates moved to the evaluation phase, and the board approved the changes. That did the trick. The additional practice helped candidates improve their teaching and freefall skills before they were tested. The board continued to tweak the evaluation scoring criteria over the next few years, and the AFF instructor rating program as it stands now is strong and producing skilled and knowledgeable AFF instructors.

Next month—Part 2, Tandem and Beyond

About the Author

About the Author

Jim Crouch was USPA Director of Safety and Training from 2000-2018. He spent months researching through old board minutes and Parachutist magazines for this article and interviewed many of those who were involved, including Jack Gregory, Mike Johnston, Rob Laidlaw, Mike Marcon, Mike Marthaller, Bill Morrissey and Paul Sitter. He also used his own personal experiences of the many changes that took place during his time at USPA.

15766